Levator Ani Avulsions: What Clinicians Need To Know

Did you know that it’s been clearly demonstrated that 10-35% (depending on sample, older moms are more at risk) of post-partum women are diagnosed with a levator avulsion and is associated with pelvic organ prolapse later in life? Levator avulsion injuries are just now starting to get their due recognition in the literature. Here’s a run-down what you need to know.

Mom’s who are at risk of having a levator avulsion:

- Are older (>33 years)

- Experiencing their first delivery

- Have a longer second stage (pushing phase) of labor

- Have higher birth-weight babes

- Have babes with a larger fetal head circumference

- Have had a forceps delivery

The highest risk factors seem to be age, first delivery, and forceps.

What you should be looking for

When women are premenopausal, symptoms of levator avulsion may be mild: vaginal laxity, decreased sexual appreciation, poor sensory awareness. As women age they are very susceptible to prolapse especially of the urethra, bladder and uterus. The larger the defect, the more likely the woman is to have signs of prolapse.GH

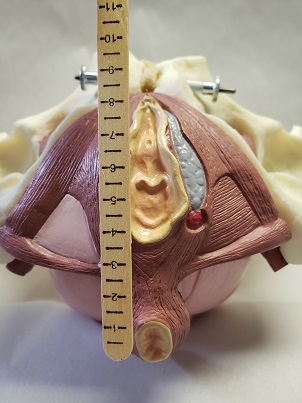

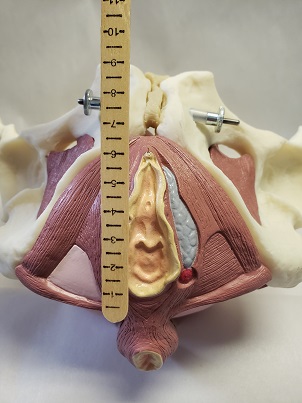

How to Measure

Researchers have identified two anatomical factors to examine. The first is termed Hiatal Ballooning. Measurements taken from the POPQ test (which is a test to determine pelvic organ prolapse and severity) are used to assess trauma to the structures surrounding the urogenital hiatus. The first measurement is called GH (genital hiatus) and it is the distance between the urethral meatus and the posterior fourchette. The second measurement is PB (perineal body) and is measured from the posterior fourchette to the anterior anus.

The GH plus PB should be less than 7 cm for any woman.

Dietz 2012 outlines the following:

>7 cm= clinical ballooning

7-7.99= mild ballooning

8-8.99= moderate ballooning

9-9.99= marked ballooning

>10 cm = severe ballooning

>8.5 cm is associated with levator avulsion

Also, this measurement should be repeated with strain (hard strain for 6 to 10 seconds). If upon strain the measurement of GH plus PB increases by more than 2-3 cm, this is indicative of a potential levator avulsion as well as connective tissue dysfunction.

Dietz also urges the experienced clinician to begin palpating for avulsion injuries. Placing the examining finger just lateral to the urethra with the pad of the finger resting on the pubic bone, a unilateral avulsion of the levator ani muscle feels like an asymmetrical loss of muscle bulk in the anterior/medial part of the muscle. When asked to perform a muscle contraction, there will be little to no contraction palpated under the examining finger. It is also recognized that the pelvic floor is capable of compensation around this injury, and areas of muscle over activity may develop, either posteriorly or contralaterally to the injury. Avulsion injuries may be bilateral as well, and as you can imagine, this would likely cause significant dysfunction and loss of support.

Levator ani avulsion injury and hiatal ballooning are independent risk factors for symptoms and signs of prolapse. We should be looking for both objective measurements. Although an avulsion will likely affect the dimensions of the urogenital hiatus, it’s probably not the only factor in the development of prolapse. It is theorized that if the muscle was damaged, there is probable connective tissue and or nerve damage as well.

What does this all mean for us as pelvic health therapists?

Let’s increase our evaluation repertoire to include palpating for avulsion injuries and measuring for hiatal ballooning. POP-QMs is a product new to CMT that is a simple to use, inexpensive, and reliable measuring stick that can make this easy for us. To learn more, click here.

We are not sure yet what the best treatment is for women with levator avulsion. We do know they are more likely to experience prolapse and that they are more likely to experience failure after prolapse surgery. When we identify women with potential avulsion and hiatal ballooning it seems clinically reasonable to consider the long-term management of stress and strain to the pelvic floor. Coaching around pressure management, pessary use, pelvic floor and accessory muscle strength and coordination, and activity modification may help decrease the need for surgery or improve outcomes after surgery.

Pulling from Dietz observation that nerve and connective tissue may also be implicated, we can borrow ideas from Neuro rehab and utilize tapping, vibration, and quick stroking to the affected muscle to help improve activation and sensory awareness.

Use caution and grace if you need to tell a patient that you suspect a muscle injury. We need to be mindful of our language. Saying, “I’m feeling that one part of your muscle is not working as well as the same muscle on the other side. Let’s see if we can get it to work better for you, or if the muscles around it can compensate” is a lot more hopeful than, “You have a torn muscle in your pelvic floor.” Dietz did a study looking at spontaneous healing of levator tears and did find 2/12 women diagnosed with a tear 3-6 months post partum were healed 2-3 years post delivery without any intervention. While we don’t have studies that show this, I can imagine that early PT intervention could only aid in the recovery of a levator avulsion.

References:

Pineda, Maylene, et al. “Can hiatal ballooning be determined by two‐dimensional trans labial ultrasound?” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 53.5 (2013): 489-493.

Dietz, H. P. “Clinical consequences of levator trauma.” Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology 39.4 (2012): 367-371.

Dietz, Hans Peter, et al. “Avulsion injury and levator hiatal ballooning: two independent risk factors for prolapse? An observational study.” Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica 91.2 (2012): 211-214.

Volloyhaug, I¹, et al. “Does levator avulsion cause distension of the genital hiatus and perineal body?.” International urogynecology journal 24.7 (2013): 1161-1165.

Khunda, Azar, Ka Lai Shek, and Hans Peter Dietz. “Can ballooning of the levator hiatus be determined clinically?.” American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 206.3 (2012): 246-e1.

Dietz, Hans Peter. “Pelvic floor trauma in childbirth.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 53.3 (2013): 220-230.

Dietz, H. P., V. Chantarasorn, and K. L. Shek. “Levator avulsion is a risk factor for cystocele recurrence.” Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology 36.1 (2010): 76-80.

Dietz, Hans Peter, et al. “Ballooning of the levator hiatus.” Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology: The Official Journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 31.6 (2008): 676-680.

Wong, V., et al. “Is levator avulsion a predictor of cystocele recurrence following anterior vaginal mesh placement?.” Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology 42.2 (2013): 230-234.

Dietz, H. P., and J. M. Simpson. “Levator trauma is associated with pelvic organ prolapse.” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 115.8 (2008): 979-984.

Jennafer Vande Vegte, MSPT, BCB-PMD, PRPC